Chiapas is a state in southern Mexico. It is a large state with remote archaeological sites deep in the jungle, national parks with sparkling mountain lakes, deep canyons, and spectacular waterfalls. It is cultural gem, with many Mayan communities preserving ancient traditions. Chiapas is about as far south as you can get in Mexico. It borders Guatemala on the southeast, the Pacific on the southwest, and the states of Oaxaca, Veracruz, and Tabasco from west to northeast.

Cities

edit- 1 Tuxtla Gutiérrez — the state capital: a large, urban area that is home to one of the world's great zoos

- 2 Boca del Cielo — a nice fishing village on the Pacific coast of the state

- 3 Catazajá — a small, sleepy village close to Palenque

- 4 Chiapa de Corzo — the oldest Spanish city in Chiapas, starting point for Sumidero Canyon boat trips

- 5 Comitán — surprisingly sophisticated, a popular weekend destination

- 6 Ocozocoautla — small town near forests, mountains, caves and other natural attractions

- 7 Ocosingo — gateway to the Mayan ruins of Toniná

- 8 Reforma Agraria – rural towm on the edge of the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve. Famous for the ecotourism center of Las guacamayas - a preservation centre of the Scarlet Macaw.

- 9 San Cristóbal de las Casas — a beautiful traditional Mayan city, lots of handicrafts, small ex-pat community

- 10 San Juan Chamula — Tsotsil indigenous village

- 11 Tapachula — Mexico's main border city with Guatemala on the Pacific coast area

Other destinations

editNature

edit

- 1 Cascadas de Agua Azul — a series of waterfalls on the Xanil River

- 2 Misol-Há — a single waterfall of 35 m in height that falls into a single, almost circular, pool amidst tropical vegetation

- 3 Cañón del Sumidero — canyon and reservoir (includes Christmas Tree Falls)

- 4 Laguna Miramar — the largest lake in the Lacandon Jungle at 40 km in diameter

- 5 El Castaño — Ecotourism in the heart of the tallest mangroves in North America

- 6 Lagunas de Montebello National Park — a national park with 59 multi-colored lakes in a pine forest and two Maya ruins

- 7 Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve — protected natural area in the Lacandon Jungle with 500 species of tree and nearly 400 species of bird

- 8 Volcan El Chichón — active volcano that was presumed dormant until violently erupting three times within a few weeks in 1982, destroying 9 villages and killing 1,900 people

- 9 Volcán Tacaná — active volcano on the border between Mexico and Guatemala, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve

Archaeological Sites

editChiapas is part of the historic territory of the Maya civilization with more than 1,000 known sites in the state. Some of the largest, most famous, and most accessible to travelers area:

- 10 Bonampak — well known for its murals and Maya ruins

- 11 Izapa — oldest, and one of the largest of the Mayan cities

- 12 Palenque — ruins that have some of the finest sculpture, architecture, roof combs, and bas-relief carvings of the Mayan era

- 13 Toniná — Maya ruins with temple-pyramids set on terraces rising 71 metres above a plaza, a large ballgame court, and over 100 carved monuments

- 14 Yaxchilán — Maya ruins known for its well-preserved sculptured stone lintels set above the doorways of the main structures

Understand

edit

The name "Chiapas" is believed to have come from the ancient city of Chiapan, which in Náhuatl means "the place where the chia sage grows".

History

editHunter gatherers began to occupy the central valley of the state around 7000 BC, but little is known about them. The oldest civilization to appear in what is now Chiapas is that of the Mokaya, who were cultivating corn and living in houses as early as 1500 BC, making them one of the oldest in Mesoamerica. There is speculation that these were the forefathers of the Olmec, who are also regarded as one of the oldest in Mesoamerica. One of the Mokaya ancient cities is now the archeological site of Chiapa de Corzo.

During the pre-Classic era, most of Chiapas was not Olmec, but had close relations with them, especially the Olmecs of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Development of this culture was agricultural villages during the pre-Classic period with city building during the Classic as social stratification became more complex. The Mayans built cities on the Yucatán Peninsula and west into Guatemala. In Chiapas, Mayan sites are concentrated along the state's borders with Tabasco and Guatemala, near Mayan sites in those entities.

Mayan civilization is marked by rising exploitation of rain forest resources, rigid social stratification, fervent local identity, and waging war against neighboring peoples. At its height, the Maya had large cities, a phonetic writing system, and development of scientific knowledge, such as mathematics and astronomy. Cities were centered on large political and ceremonial structures elaborately decorated with murals and inscriptions. Among these cities are Palenque, Bonampak, Yaxchilan, Chinkultic, Toniná and Tenón. The Mayan civilization had extensive trade networks and large markets.

Nearly all Mayan cities collapsed around the same time, 900 AD. It is not known what ended the civilization but theories range from over population size, natural disasters, disease, and loss of natural resources through over-exploitation or climate change. From then until the Spanish conquest in the early 16th century, social organization of the region fragmented into much smaller units and social structure became much less complex.

The first contact between Spaniards and the people of Chiapas came in 1522, when Hernán Cortés sent tax collectors to the area after the Aztec Empire was subdued. By 1530 almost all of the indigenous peoples of the area had been subdued with the exception of the Lacandons in the deep jungles who actively resisted until 1695. The first Spanish city, today called San Cristóbal de las Casas, was established in 1528.

Soon after, the encomienda system was introduced, which reduced most of the indigenous population to serfdom and many as slaves as a form of tribute and way of locking in a labor supply for tax payments. New diseases brought by the conquistadors and overwork on plantations dramatically decreased the indigenous population. The Spanish established missions, mostly under the Dominicans. The Dominican evangelizers became early advocates of the indigenous' people's plight, and got a law passed in 1542 for their protection. The encomienda system that had perpetrated much of the abuse of the indigenous peoples declined by the end of the 16th century, and was replaced by haciendas. However, the use and misuse of Indian labor remained a large issue in Chiapas politics into modern times.

The Spanish introduced new crops such as sugar cane, wheat, barley and indigo as main economic staples alongside native ones such as corn, cotton, cacao and beans. Livestock such as cattle, horses and sheep were introduced as well. Most Europeans and their descendants tended to concentrate in cities such as Ciudad Real, Comitán, Chiapa and Tuxtla. Intermixing of the races was prohibited by colonial law, but widely ignored, and by the end of the 17th century there was a significant mestizo population. Added to this was a population of African slaves brought in by the Spanish in the middle of the 16th century due to the loss of native workforce.

During the Mexican War of Independence in the 1810s, a group of influential Chiapas merchants and ranchers sought the establishment of the Free State of Chiapas. However, this alliance did not last as the lowlands preferred inclusion among the new republics of Central America, and the highlands annexation to Mexico. In 1821, a number of cities in Chiapas declared the state's separation from the Spanish empire. With the exception of the pro-Mexican Ciudad Real (San Cristóbal) and some others, many Chiapanecan towns and villages favored a Chiapas independent of Mexico and some favored unification with Guatemala. Elites in highland cities pushed for incorporation into Mexico. In 1822, Emperor Agustín de Iturbide decreed that Chiapas was part of Mexico, but the Soconusco region maintained a neutral status until 1842, when Oaxacans occupied the area, and declared it reincorporated into Mexico.

In the decades after the end of the war, the state's society evolved into three distinct spheres: indigenous peoples, mestizos from the farms and haciendas, and the Spanish colonial cities. Most of the political struggles were between the latter two groups especially over who would control the indigenous labor force.

Liberal land reforms of the 19th century had negative effects on the state's indigenous population unlike in other areas of the country. Liberal governments expropriated lands that had been held by the Spanish Crown and Catholic Church in order to sell them into private hands. However, many of these lands had been in a kind of "trust" with the local indigenous populations, who worked them. Many of these lands fell into the hands of large landholders who then made the local Indian population work for three to five days a week just for the right to continue to cultivate the lands. Many became "free" workers on other farms, but they were often paid only with food and basic necessities from the farm shop. If this was not enough, these workers became indebted to these same shops and then unable to leave.

The opening up of these lands also allowed many whites and mestizos to encroach on what had been exclusively indigenous communities in the state. The changing social order had severe negative effects on the indigenous population including alcoholism and indebtedness. One other effect that liberal land reforms had was the start of coffee plantations, especially in the Soconusco region. The land reforms brought colonists from other areas of the country as well as foreigners from England, the United States and France. These immigrants introduced coffee production and modern machinery. Eventually, this production of coffee would become the state's most important crop.

In 1891 Governor Emilio Rabasa took on the local and regional landowners and centralized power into the state capital. He modernized public administration, transportation and promoted education. He also changed state policies to favor foreign investment and land consolidation for the production of cash crops such as henequen, rubber, guayule, cochineal and coffee. The economic expansion and investment in roads also increased access to tropical commodities such as hardwoods, rubber and chicle.

These new crops required cheap and steady labor to be provided by the indigenous population. By the end of the 19th century, the four main indigenous groups, Tzeltals, Tzotzils, Tojolabals and Ch’ols were living in "reducciones" or reservations, isolated from one another. Conditions on the farms of this era was serfdom, leading to the Mexican Revolution. While this coming event would affect the state, Chiapas did not follow the uprisings in other areas.

In the early 1930s, Governor Victorico Grajales pursued President Lázaro Cárdenas' social and economic policies including persecution of the Catholic Church. These policies would have some success in redistributing lands and organizing indigenous workers but the state would remain relatively isolated for the rest of the 20th century.

There was political stability from the 1940s to the early 1970s. In the mid-20th century, the state experienced a significant rise in population, which outstripped local resources, especially land in the highland areas. Economic development in general raised the output of the state, especially in agriculture, but it had the effect of deforesting many areas, especially the Lacandon. Added to this was there were still serf-like conditions for many workers and insufficient educational infrastructure. Population continued to increase faster than the economy could absorb. In Chiapas poor farmland and severe poverty afflicted the Mayan indigenous population which led to unsuccessful non-violent protests and eventually armed struggle started by the Zapatista National Liberation Army in January 1994.

These events began to lead to political crises in the 1970s, with more frequent land invasions and takeovers of municipal halls. This was the beginning of a process that would lead to the emergence of the Zapatista movement in the 1990s.

In the 1980s, a large wave of refugees came into the state from Central America as a number of these countries, especially Guatemala, were in the midst of political turmoil. The arrival of thousands of refugees politically destabilized Chiapas. Camps were established in Chiapas and other southern states, and mostly housed Mayan peoples. However, most Central American refugees from that time received no official status, estimated by church and charity groups at about half a million from El Salvador alone.

In the 1980s, the politicization of the indigenous and rural populations of the state that began in the 1960s and 1970s continued. In 1980, several communal land organizations joined to form the Union of Unions. It had a membership of 12,000 families from over 180 communities. By 1988, this organization took over much of the Lacandon Jungle portion of the state. Most of the members of these organization were from Protestant and Evangelical sects as well as "Word of God" Catholics affiliated with the political movements of the Diocese of Chiapas. What they held in common was indigenous identity vis-à-vis the non-indigenous.

The adoption of liberal economic reforms by the Mexican federal government clashed with the leftist political ideals of these groups, notably as the reforms were believed to have begun to have negative economic effects on poor farmers, especially small-scale indigenous coffee-growers. Opposition coalesced into the Zapatista movement in the 1990s. Although the area has extensive resources, much of the local population of the state, especially in rural areas, did not benefit from this bounty. In the 1990s, two thirds of the state's residents did not have sewage service, only a third had electricity and half did not have potable water. Over half of the schools offered education only to the third grade and most pupils dropped out by the end of first grade.

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) came to the world's attention when on January 1, 1994, EZLN forces occupied and took over seven towns. Although it has been estimated as having no more than 300 armed guerrilla members, the EZLN paralyzed the Mexican government, and the rebellion became a national protest against the government. The armed conflict was brief, mostly because the Zapatistas did not try to gain traditional political power. They focused more on trying to manipulate public opinion in order to obtain legal and economic concessions from the government.

As of the first decade of the 2000s the Zapatista movement remained popular in many indigenous communities. The Zapatista movement has had some successes. The agricultural sector of the economy now favors commonly-owned land. In the last decades of the 20th century, Chiapas's traditional agricultural economy has diversified somewhat with the construction of more roads and better infrastructure by the federal and state governments. Tourism has become important in some areas of the state, especially in San Cristóbal de las Casas and Palenque. However, Chiapas remains one of the poorest states in Mexico.

Read

edit- The Lawless Roads by Graham Greene. Graham Greene describes his journey to San Cristobal de las Casas through Chiapas and Tabasco in the 1930s. (ISBN 0140185801)

- The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene. A whiskey priest, a corrupt church, and Chiapas all set in one of Greene's most powerful books. (ISBN 0140184996)

Talk

editMost people will speak Spanish, but this is less common among the indigenous peoples, where Mayan languages are common, including significant numbers who speak the Tsotsil and Tseltal Mayan variants. Very few can speak English, almost always very badly.

Get in

editBy plane

editBy bus

editBuses are the most common way to travel in this region. Most intercity buses from other parts of southern Mexico will serve Tuxtla Gutierrez where you can transfer to smaller regional bus lines to reach smaller towns and other destinations. The most extensive bus service in Chiapas is provided by ADO, which operates several company bus stations in smaller markets and has routes from Villahermosa (M$460 as of January 2023), Ciudad del Carmen, Campeche, Oaxaca, and Coatzalcoalcos in southern Veracruz.

First-class buses can also be used to travel from major Central America cities to Chiapas using TicaBus, which serves the Tapachula bus station. Other Guatemalan bus companies also serve Tapachula.

By car

editThe most flexible way to get in and around in Chiapas is by renting a car and driving. Some major routes are toll roads. Important highways coming into Chiapas include:

- MEX 190 goes from Oaxaca to Tuxtla Gutierrez.

- MEX 145D goes from Coatzalcoalcos, Veracruz to Tuxtla Gutierrez.

- MEX 195 goes from Villahermosa, Campeche to Tuxtla Gutierrez.

By train

editGet around

editThe easiest way to get around within cities is probably by private car, taxi, or colectivo. Colectivos are small vans or buses that are very cheap and follow specific routes. The main destinations on the route of each colectivo are listed on the right side of its windshield, though it is sometimes hard to tell if it is really going your way. Asking the driver usually works, but don't expect him or her to speak English.

Outside of cities, the best way to get around is by private car, bus (slow, with frequent stops), colectivo (a little more expensive than in the city), taxis, or pickups (camionetas). Taxis outside of cities charge very high rates if it is not their regular route, so make sure the driver knows you do not want a viaje especial (special trip). Sharing taxis is very common, and almost universal outside cities. The pickups that are for public transportation are usually identifiable. Try to get a seat in the cab, unless you enjoy being pressed against a large group of sweaty locals in the hot sun. Pickups are also fairly slow and make frequent stops, but they are faster than the bus.

See

edit

There are three main tourist routes: the Maya Route, the Colonial Route and the Coffee Route.

The Maya Route runs along the border with Guatemala in the Lacandon Jungle and includes the sites of Palenque, Bonampak, Yaxchilan along with the natural attractions of Agua Azul Waterfalls, Misol-Há Waterfall, and the Catazajá Lake. Palenque is the most important of these sites, and one of the most important tourist destinations in the state. Yaxchilan was a Mayan city along the Usumacinta River. It developed between 350 and 810 CE. Bonampak is known for its well preserved murals. These Maya sites have made the state an attraction for international tourism. These sites have many of structures, most of which date back thousands of years, especially to the 6th century. In addition to the sites on the Mayan Route, there are others within the state away from the border such as Toniná, near the city of Ocosingo.

The Colonial Route is mostly in the central highlands with a significant number of churches, monasteries and other structures from the colonial period along with some from the 19th century and into the early 20th. The most important city on this route is San Cristóbal de las Casas, located in the Los Altos region in the Jovel Valley. The historic center of the city is filled with tiled roofs, patios with flowers, balconies, Baroque facades along with Neoclassical and Moorish designs. It is centered on a main plaza surrounded by the cathedral, the municipal palace, the Portales commercial area and the San Nicolás church. In addition, it has museums dedicated to the state's indigenous cultures, one to amber and one to jade, both of which have been mined in the state. Other attractions along this route include Comitán de Domínguez and Chiapa de Corzo, along with small indigenous communities such as San Juan Chamula. The state capital of Tuxtla Gutiérrez does not have many colonial era structures left, but it lies near the area's most famous natural attraction of the Sumidero Canyon. This canyon is popular with tourists who take boat tours into it on the Grijalva River to see such features such as caves (La Cueva del Hombre, La Cueva del Silencio) and the Christmas Tree, which is a rock and plant formation on the side of one of the canyon walls created by a seasonal waterfall.[90][131]

The Coffee Route begins in Tapachula and follows a mountainous road into the Suconusco regopm. The route passes through Puerto Chiapas, a port with modern infrastructure for shipping exports and receiving international cruises. The route visits a number of coffee plantations, such as Hamburgo, Chiripa, Violetas, Santa Rita, Lindavista, Perú-París, San Antonio Chicarras and Rancho Alegre. These haciendas provide visitors with the opportunity to see how coffee is grown and initially processed on these farms. They also offer a number of ecotourism activities such as mountain climbing, rafting, rappelling and mountain biking. There are also tours into the jungle vegetation and the Tacaná Volcano. In addition to coffee, the region also produces most of Chiapas’ soybeans, bananas and cacao.

The state has many ecological attractions, most of which are connected to water. The main beaches on the coastline include Puerto Arista, Boca del Cielo, Playa Linda, Playa Aventuras, Playa Azul and Santa Brigida. Others are based on the state's lakes and rivers. Laguna Verde is a lake in the Coapilla municipality. The lake is generally green but its tones constantly change through the day depending on how the sun strikes it. In the early morning and evening hours there can also be blue and ochre tones as well. The El Chiflón Waterfall is part of an ecotourism center located in a valley with reeds, sugarcane, mountains and rainforest. It is formed by the San Vicente River and has pools of water at the bottom popular for swimming. The Las Nubes Ecotourism center is located in the Las Margaritas municipality near the Guatemalan border. The area features a number of turquoise blue waterfalls with bridges and lookout points set up to see them up close.

Still others are based on conservation, local culture and other features. The Las Guacamayas Ecotourism Center is in the Lacandon Jungle on the edge of the Montes Azules reserve. It is centered on the conservation of the red macaw, which is in danger of extinction. The Tziscao Ecotourism Center is centered on a lake with various tones. It is located inside the Lagunas de Montebello National Park, with kayaking, mountain biking and archery. Lacanjá Chansayab is located in the interior of the Lacandon Jungle and a major Lacandon people community. It has some activities associated with ecotourism such as mountain biking, hiking and cabins. The Grutas de Rancho Nuevo Ecotourism Center is centered on a set of caves in which appear capricious forms of stalagmite and stalactites. There is horseback riding as well.

Do

editVolunteering

edit- Volunteer as a Human Rights Observer in the autonomous Zapatista communities contact Capise (brigadas@capise.org.mx) for short (5 days) activities or for longer volunteership contact Frayba .

- Participate as a volunteer or group coordinator on sustainable projects in Maya communities. The NGO NATATE focuses on the following fields: alternative technologies, waste management, water(capture and filtering), Education, reforestation, construction. Opportunities are available for short and long term voluntary service.

Buy

editLocal artisans produce several unique items of popular folk art that are different from other regions. Chiapas is known for its woven cloths that feature exquisite embroidery. They are also known for their ceramics and jewelry.

The jewelry made in Chiapas is often based on amber and feature Maya symbols and designs. This is quite different from the silver jewelry found in most Mexican states.

Ceramic production is most commonly associated with the town of Amantengo del Valle where everything from fine decorative ceramics to functional terracotta pots is made. In the artesania markets you will often find locally made figurines of jaguars, parrots, or other animals painted in colors and patterns distinctive to the Maya culture.

Eat

editLike the rest of Mesoamerica, the basic diet has been based on corn, and Chiapas cooking retains strong indigenous influence. One important ingredient is chipilin, a fragrant and strongly flavored herb and hoja santa, the large anise-scented leaves used in much of southern Mexican cuisine. Chiapan dishes do not incorporate many chili peppers as part of their dishes. Rather, chili peppers are most often found in the condiments. One reason for that is that a local chili pepper, called the simojovel, is far too hot to use except very sparingly. Chiapan cuisine tends to rely more on slightly sweet seasonings in their main dishes such as cinnamon, plantains, prunes and pineapple are often found in meat and poultry dishes.

Tamales are a major part of the diet and often include chipilín mixed into the dough and hoja santa, within the tamale itself or used to wrap it. One tamale native to the state is the "picte", a fresh sweet corn tamale. Tamales juacanes are filled with a mixture of black beans, dried shrimp, and pumpkin seeds.

Meats are centered on the European introduced beef, pork and chicken as many native game animals are in danger of extinction. Meat dishes are frequently accompanied by vegetables such as squash, chayote and carrots. Black beans are the favored type. Beef is favored, especially a thin cut called tasajo usually served in a sauce. Pepita con tasajo is a common dish at festivals especially in Chiapa de Corzo. It consists of a squash seed based sauced over reconstituted and shredded dried beef. As a cattle raising area, beef dishes in Palenque are particularly good. Pux-Xaxé is a stew with beef organ meats and mole sauce made with tomato, chili bolita and corn flour. Tzispolá is a beef broth with chunks of meat, chickpeas, cabbage and various types of chili peppers. Pork dishes include cochito, which is pork in an adobo sauce. In Chiapa de Corzo, their version is cochito horneado, which is a roast suckling pig flavored with adobo. Seafood is a strong component in many dishes along the coast. Turula is dried shrimp with tomatoes. Sausages, ham and other cold cuts are most often made and consumed in the highlands.

In addition to meat dishes, there is chirmol, a cooked tomato sauced flavored with chili pepper, onion and cilantro and zats, butterfly caterpillars from the Altos de Chiapas that are boiled in salted water, then sautéed in lard and eaten with tortillas, limes, and green chili pepper.

Sopa de pan consists of layers of bread and vegetables covered with a broth seasoned with saffron and other flavorings. A Comitán speciality is hearts of palm salad in vinaigrette, and Palenque is known for many versions of fried plaintains, including filled with black beans or cheese.

Cheese making is important, especially in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Rayon and Pijijiapan. Ocosingo has its own self-named variety, which is shipped to restaurants and gourmet shops in various parts of the country. Regional sweets include crystallized fruit, coconut candies, flan and compotes. San Cristobal is noted for its sweets, as well as chocolates, coffee and baked goods.

Drink

editWhile Chiapas is known for good coffee, there are a number of other local beverages. The oldest is pozol, originally the name for a fermented corn dough. This dough has its origins in the pre-Hispanic period. To make the beverage, the dough is dissolved in water and usually flavored with cocoa and sugar, but sometimes it is left to ferment further. It is then served very cold with much ice. Taxcalate is a drink made from a powder of toasted corn, achiote, cinnamon and sugar prepared with milk or water. Pumbo is a beverage made with pineapple, club soda, vodka, sugar syrup and much ice.

Pox

editPox is a fascinating distilled spirit with deep roots in the Tzotzil Mayan culture. The drink is a cross between whisky and rum being based on both grain and sugar cane. Most pox is fairly light in color and flavor and resembles rum more closely than it does whisky. Traditionally, the grain used to produce pox was corn and mostly traditional heritage varieties connected to Tzotzil rituals. Modern producers frequently dispense with tradition and instead use cheap GMO corn, or worse, no corn at all. The sugar used in pox is generally in the form of piloncillo, a crude (relatively unprocessed) brown sugar. Although pox is bottled and exported to other countries (including the U.S.), the mass market export varieties are invariably inferior, made with cheap ingredients using shortcut industrial processes. Good, well-crafted pox rarely travels outside Chiapas.

Pox is bottled young (unaged) and is a clear spirit, typically 80 to 100 proof (40-50% alcohol). Good pox can be sampled neat, though it is good in most cocktails that call for rum (particular tropical drinks like mai tai or daiquiri).

Tasting a well-made traditional pox reveals a drink with more complexity than a typical white rum. The pox often has smoky notes, though this isn't from any roasting process, but rather is contributed by the heritage varieties of corn and is a signature of a good pox.

Flavored varieties are common throughout Chiapas, typically herbs and spices or fruits. Some common flavored poxes include: cocoa, hibiscus (jamaica), rosemary, tamarind, and mango.

Stay safe

edit

Be aware of your personal belongings all the time, and do not walk with jewelry and expensive objects in sight. Chiapas is usually a secure state, where the warmth of people will make you feel at home.

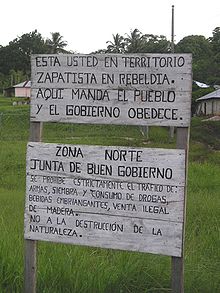

Much of the northeastern portion of Chiapas is fully or partially under the protection of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, or the EZLN. These areas have declared themselves as autonomous, and are referred to as the Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities, or MAREZ. The EZLN have been in this area since 1 January 1994, the day that NAFTA went into effect. Though they might wear black masks and carry guns, they likely will not harm you unless you are shouting praises of the Mexican army. The EZLN are not a gang or cartel; they are a decentralized organization dedicated to libertarian socialist principles who oppose the exploitative capitalist practices and destructive environmental policies of the Mexican government. Many of the people living under the Zapatista umbrella support their presence, as they provide many essential public services that the Mexican government has been unable, or unwilling, to provide. Though relations between the EZLN and the Mexican government have been rather peaceful in the 21st century, skirmishes between them have been known to occur. There are also anti-Zapatista militias who have carried out massacres of EZLN members and suspected sympathizers. Respect their rules when you are in their territory, stay aware of any potential flashpoints, and you will probably be fine.

Go next

edit- Oaxaca - 10 hours on the bus.

- Guatemala - About 10 hours to Guatemala City.

- Tabasco - About 4 hours to Villahermosa.

- Campeche - About 10 hours on the bus.

- Regular flights to Mexico City, Guadalajara and other major destinations in Mexico.