| WARNING: Since 2011, the country has experienced two devastating civil wars, both of which have caused widespread destruction and displacement. The Libyan government is very unstable and has a weak grip over the whole country. Many governments recommend against all travel to Libya, and are unable to provide consular assistance. | |

Government travel advisories

| |

| (Information last updated 19 Aug 2024) |

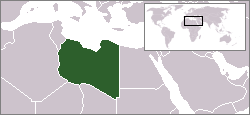

Libya (Arabic: ليبيا, Libiya) is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa and a part of the Arab world. Although the country is rich in history and culture and has great tourism potential, the country has been in the news for all the wrong reasons since the 1960s. Since the 2010s, the country has been in a state of flux and is rather dangerous to travel to.

However, under less extreme circumstances, this vast country has a lot to offer to the adventurous, thrill-seeking traveller, from deserts to historical ruins from various historical periods. Libya is a difficult country to get around, but the rewards for the persistent visitor are unforgettable.

If you do decide to visit, know that there's a lot to do and see in Libya; in fact, you might be showered with a lot of hospitality and care, even if you unintentionally make a few cultural blunders.

Regions

edit

| Cyrenaica (Benghazi, Shahhat, Tobruk) The north-eastern region on the Mediterranean Sea. |

| Saharan Libya (Gaberoun, Ghadamis, Sabha, Ghat) Huge southern desert region with amazing scenery and some of the hottest temperatures recorded anywhere in the world. |

| Tripolitania (Tripoli, Surt, Zuwara) The north-western region on the Mediterranean Sea with the capital city and ancient Roman ruins. |

Cities

edit- 1 Tripoli (طرابلس) — the capital and largest city of Libya. The traveller's main entry point.

- 2 Benghazi (بنغازي) — the largest city of Cyrenaica and the second largest of the country

- 3 Ghadamis (غدامس) — an oasis town with a large Berber population. The old part of the town is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- 4 Sabha (سبها) — an oasis city approximately 640 km (400 mi) south of Tripoli

- 5 Shahhat (شحات) — Ancient city of Cyrene, a World Heritage site, is nearby

- 6 Sirte (سِرْت) — the birthplace of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya's longtime ruler.

- 7 Tobruk (طبرق) — harbour town with World War II cemeteries

- 8 Zuwara (زوارة) — a port city in the northwest not far from the Tunisian border

- 9 Misrata (مصراتة) — Libya's commercial hub

Other destinations

edit- 1 Gaberoun — small former Bedouin village on a wonderful oasis, around 150 km west of Sabha

- 2 Ghat — an ancient settlement in the south west with prehistoric rock paintings and very challenging desert trekking

- Green Mountain

- 3 Leptis Magna — extensive Roman ruins

- Nafusa mountains

- 4 Sabratha – a UNESCO World Heritage Site on the Mediterranean coast in northwestern Libya.

Understand

editPolitics and government

editLibya is officially known as the State of Libya (Arabic: دولة ليبيا; Dawlat Libiya).

Until 2011, the country was known as the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (Arabic: الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الإشتراكية العظمى; al-Jamāhīrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha'bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah al-'Uẓmá).

Geography

editLibya is Africa's 4th largest country, covering nearly 1,800,000 square kilometres (690,000 sq mi) of land (similar to Alaska). While the country's northern parts are densely populated, the southern parts are barren, poorly developed, and virtually uninhabited. In all, Libya has some 7 million inhabitants, making it one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world.

History

editAncient history

edit

Archaeological evidence indicates that from as early as 8,000 BC, the coastal plain of Ancient Libya was inhabited by a Neolithic people, the Berbers, who were skilled in the domestication of cattle and the cultivation of crops. Later, the area known in modern times as Libya was also occupied by a series of other peoples, with the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Persian Empire, Romans, Vandals, Arabs, Turks and Byzantines ruling all or part of the area.

Italian colonial era

editFrom 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was split into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania, run by Italian governors. During the Italian colonial period, between 20% and 50% of the Libyan population died in the struggle for independence, and some 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting roughly one-fifth of the total population.

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the name of the colony (made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). King Idris I, Emir of Cyrenaica, led Libyan resistance to Italian occupation between the two world wars. Following Allied victories against the Italians and Germans, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were under British administration, from 1943 to 1951, while the French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.

Kingdom of Libya

editAfter gaining independence from Italy in the 1950s, Libya became a constitutional monarchy headed by King Idris. Under his reign, Libya espoused a pro-Western foreign policy and forged close ties with the United States and the United Kingdom. Libya's first-ever university was established in Tripoli, and Libya became a member state of the United Nations and the Arab League.

The discovery of large oil reserves in 1959 brought considerable wealth to the country and enabled Libya to transition to a wealthy country from one of the world's poorest countries. However, much of the oil wealth fell into the hands of Idris' inner circle, which strengthened negative sentiments towards the Libyan monarchy.

Libya under Muammar al-Gaddafi

editBy the 1960s, the Libyan monarchy became increasingly unpopular. More and more Libyans grew convinced that the Libyan monarchy was highly corrupt, inefficient at governing the country effectively, and weak. The rise of pan-Arab nationalism in the Middle East also contributed to negative sentiments towards the Libyan monarchy.

On September 1, 1969, a group of military officers led by Muammar Gaddafi − who was 27 years old and a captain in the Libyan army at the time − overthrew King Idris in a bloodless coup d’état. Having taken power, Gaddafi abolished the monarchy, kicked out Western military bases, deported the country's Italian population, and proclaimed the new Libyan Arab Republic, which was a military dictatorship in disguise.

In the late 1970s, Libya became known as the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and Gaddafi styled himself as the 'Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution'. This was a significant change, as it marked Libya's transition from a republic to an Islamic socialist state based on Gaddafi's personal political beliefs and philosophies.

The Gaddafi regime made a host of reforms, directing funds toward providing education, healthcare and housing for all, passing laws of equality of the sexes, criminalising child marriage and insisting on wage parity, although it also brutally put down all signs of dissent and promoted a cult of personality. Per capita income in the country rose to the fifth highest in Africa. Gaddafi engaged in support of, as he put it, "anti-imperialist and anti-colonial movements". During the 1980s and 1990s, Libya supported rebel movements such as ANC, PLO and the Polisario.

In early 2011, as part of the Arab Spring that attempted to turn the Arab countries into liberal democracies, the authority of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya government was challenged by protesters, leading to a civil war, where NATO-led forces intervened with air strikes, military training and material support to the rebels.

On 20 October 2011 Muammar Gaddafi was killed by elements of the National Transition Council following his capture on a roadside in his hometown of Sirte. On 23 October the liberation of Libya was pronounced by the National Transition Council.

Present history

editAfter 2011, Libya soon entered a civil war due to the disputes between the several armed groups that gained power during the insurrection. In September 2012, an attack of the Ansar al-Shariah extremist group on the U.S. embassy resulted in the death of the American ambassador and other public officers. In April 2016, U.S. president Barack Obama said that failing to prepare Libya for the aftermath of the ousting of Gaddafi was "the worst mistake of his presidency".

Libya remains deeply politically and economically unstable. Until March 2021, there were two rival governments: the Government of National Accord (internationally recognised), based in Tripoli, which controlled most of the West of the country, and the Council of Representatives, based in Tobruk, which controlled most of the east. These two governments, however, had limited control over the territory, a large part of it being effectively ruled by tribal warlords and extremist groups such as ISIS and Ansar al-Shariah.

A ceasefire took effect in October 2020, and the Government of National Unity assumed power from the rival governments. The main groups agreed to elections being held on 24 Dec 2021, but the elections were repeatedly postponed and there has been sporadic fighting between the different armed groups. The situation remains unresolved and volatile as of 2024. Governmental institutions are controlled by different fractions, which don't necessarily communicate well among each other.

There are hundreds of thousands of displaced people and food shortages are commonplace. Slavery has also made a return since the ousting of Gaddafi, with numerous slave markets now operating openly in various parts of the country.

Religion

editIslam is the dominant religion in the country, practised by approximately 97% of the population. Most Libyans are Sunni Muslims.

Christianity is the second largest religion in the country, practised by approximately 2.7% of the population. Most Christians are followers of the Coptic Church.

Buddhism is practised by 0.3% of the population and it is believed that Libya has the largest Buddhist population in North Africa.

At some point in history, Libya was home to one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world and it is believed that Judaism came to Libya sometime during 400–300 BC. During World War II and the Gaddafi years, many Libyan Jews fled the country in search of a better life elsewhere.

Climate

editWithin Libya as many as five different climatic zones have been recognised, but the dominant climatic influences are Mediterranean and Saharan. In most of the coastal lowland, the climate is Mediterranean, with warm summers and mild winters. Rainfall is scanty. The weather is cooler in the highlands, and frosts occur at maximum elevations. In the desert interior the climate has very hot summers and extreme diurnal temperature ranges.

Get in

edit |

Visa restrictions:

Entry will be denied to citizens of Israel, Bangladesh, Iran, Pakistan, Yemen, Sudan and Syria.

If your passport shows any proof of having visited Israel (e.g. Israeli stamps and visas), you will be denied entry. Citizens of South Korea are banned from visiting the country without permission from the South Korean government. |

| Note: In 2012, Libya decided to "temporarily" close its borders with Sudan, Chad, Niger & Algeria with the purported aim of stifling traffic in illegal immigrants, drugs, and armed groups (including those associated with al Qaeda and other extremists). The southern regions Ghadames, Ghat, Obari, Al-Shati, Sebha, Murzuq and Kufra have been declared "closed military zones to be ruled under emergency law". Even in better times these borders were considered risky due to armed bandits and criminals associated with human and drug trafficking. | |

Entry requirements

editLibya is a very difficult country to access, mainly because its immigration requirements are notoriously perplexing. The Libyan government has a history of changing its immigration rules frequently and without warning.

The government officially launched an e-Visa system on 21 March 2024.

Tourism requirements

editVisitors travelling to Libya for tourism are required to convert US$1,000, or equivalent, in freely convertible cash or debit the amount from a valid credit card upon arrival. Failure to do so will result in you being denied entry. There are, however, a few exceptions to this rule:

- Those travelling as part of a guided tour.

- Those who have been sponsored by a Libyan citizen.

Entry bans

editCitizens of Israel, Bangladesh, Iran, Pakistan, Yemen, Sudan and Syria are banned from entering Libya.

- The Libyan government appears to be convinced that Bangladeshi citizens regularly abuse Libyan immigration rules just so that they can emigrate to Europe from Libya.

- The Libyan government appears to be convinced that Sudan and Syria are involved in "undermining" Libya’s security and sovereignty.

- The Libyan government appears to be convinced that Iranian, Yemeni, and Pakistani citizens often join Islamic terror groups.

- Due to the Arab-League boycott of Israel, citizens of Israel and those who have visited Israel are forbidden from entering the country.

Special requirements

editIf you are a citizen of the United States, you are required to be sponsored by a Libyan company before coming to Libya.

By plane

editMost visitors normally enter Libya by plane.

Ever since the civil war began, air operations have become quite unreliable as airports are repeatedly closed and opened again depending on the level of violence in the area.

- 1 Tripoli International Airport (TIP IATA). Tripoli International Airport (Arabic: مطار طرابلس العالمي), is the nation's largest airport and is in the town of Ben Ghashir. The airport is closed and non-operational.

- 2 Mitiga International Airport (MJI IATA), ☏ +218 21 350 3405, contact@mitiga-airport.ly. An international airport serving Tripoli. Has flights going to countries like Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, and Turkey.

- 3 Misrata Airport (MRA IATA), airportmisurata6@gmail.com. An international airport serving Misrata. Has flights going to countries like Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, and Turkey.

The Benina International Airport, (BEN IATA), (Arabic: مطار بنينة الدولي) is in the town of Benina, 19 km east of Benghazi.

Libya has several other airports, but many of them may remain closed:

By train

editBy car

editLibya shares borders with six countries: Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Chad, Niger, and Sudan.

For travel to Libya overland, there are bus and "shared taxi" (accommodating 6 people in a station wagon) services from such places as Tunis, Alexandria, Cairo and Djerba.

There are accounts of people having done the trip in their own 4x4s or using their own dirt bikes and campervans. There are very few border posts open to travel into the country with a foreign car: Ras Jdayr (from Tunisia) and Bay of As Sallum (from Egypt). At the border, you must buy a temporary licence including a number plate.

From Niger

editThe Libya-Niger border is often described as an "ungoverned area", i.e, a region with limited government presence. Moreover, areas near the Libya-Niger border are hotspots for terrorism, human trafficking, smuggling, and organised crime. Given Libya's proximity to Europe, many migrants from Niger often try to sneak in.

If you have no knowledge of Libyan roads, Nigerien roads, or both and if you have no experience with driving in harsh climates, you should not drive into Libya from Niger.

From Chad

editAreas near the Libya-Chad border are hotspots for terrorism, militancy, human trafficking, smuggling, and organised crime. In addition to these issues, relations between Chad and Libya are incredibly unhealthy and the Libyan authorities often close the Libyan-Chadian border without prior warning.

From Sudan

editGiven the poor security and political situation in Sudan, travelling overland from Sudan to Libya is not recommended.

By bus

editBy boat

editSupposedly, in 2023, there is a ferry, the Kevalay Queen, connecting Tripoli and Misrata with Istanbul.

Previous scheduled services may take an extended time to restore, please check before ticketing for any service.

Get around

edit

By plane

edit| Note: Airline operations have become quite unreliable since the 2010s. You are advised to monitor local media as high levels of violence in an area can cause airport operations to shut down for an indefinite period. | |

Due to the immense size of the country, the terrible state of the roads, and the poor security situation, the only way to get around the country quickly is by plane. This is not to say that it's entirely safe, but it's still a better alternative to travelling overland.

By road

editPrior to the civil war many visitors undertook the trip in their own 4x4s or using their own dirt bikes and campervans. It would seem that they encountered considerable hospitality once in the country. It was not uncommon to see convoys of European campervans on Libya's highways prior to the civil war. Please make serious and detailed enquiries prior to undertaking any trip by road into Libya to determine if the area you will be travelling through is safe and if fuel and other services are available. Travel such as this is not recommended.

Some self-drive car rental services are available in the large cities but the rates were typically high and the cars unreliable. Avis and Europcar provide rental cars. Around the major cities, driving can be an "education", although driving standards are not as bad as in other countries in the region.

The recommended method of transport for tourists around major towns is taxis. There are also many shared taxis and buses. The small black and white taxis (or death pandas) tend to be safer (more cautious drivers) but learn the term "Shweyah-Shweyah", Libyan for slow-down, and ask them to keep off Al-Sareyah (the motorway from Souq-Al-Thataltha to Janzour)! A taxi driver will routinely try it on with tourists. Will always try to charge 10 dinars for a fare around town. Negotiate the price first. If you find a good taxi driver with a good car, it doesn't hurt to build up a relationship and get their mobile number. Taxis from the airport can be more expensive as the airport is a long way from town. The Corinthia Hotel runs a shuttle from the airport to the hotel.

Longer journeys such as Tripoli to Benghazi will take about 14 hours by bus. The buses make stops for meals and the very important tea (shahee) breaks along the way. A faster method is to take the "shared taxis" but some of the drivers tend to be more reckless in order to cut the travel time. Services such as inter-city bus services have been seriously disrupted or halted due to the civil unrest and armed conflict. Travel by long distance bus services in Libya is not recommended.

If travelling by road in post liberation Libya very high levels of situational awareness should be practised at all times. Fuel supplies and vehicle repair services may be disrupted and some roads and bridges may be damaged. Armed groups and dis-affected individuals, armed militias and detachments of foreign military and military contractors are active throughout Libya. The opportunity to inadvertently become involved in a violent confrontation or robbery is much higher than in many other countries in the region and caution should be exercised. If in doubt stop and take cover or if possible immediately depart the area to a safer location.

Talk

edit- See also: Arabic phrasebook

The official language of Libya is Arabic .

The local vernacular is Libyan Arabic. It has extensive borrowings from languages such as Italian, Turkish, and Amazigh/Tamazight ("Berber"). For instance, the word for traffic light is "semaforo" and the word for petrol is "benzina". Modern Standard Arabic is rarely spoken in everyday conversations. However, most Libyans are knowledgeable in MSA, so if you wish to improve your Arabic skills, you shouldn't have any problems. You're not expected to know the local dialect, but if you make an attempt to learn a few words of the local vernacular, you will impress the locals!

English is the most widely taught foreign language in Libyan schools and it is widely used in commerce. You should not have problems getting around using only English, but the downside of speaking English is that you'll immediately be identified as an outsider and may attract unwanted attention from some undesirable people (e.g. criminals, corrupt officials). Outside of Tripoli, however, English is probably rarely used.

Although Libya was once an Italian colony, the use of Italian has diminished drastically since independence. Very few people (apart from the elderly, the well-educated, members of the Italian community, and businesspeople) nowadays speak Italian.

See

edit

Libya's colourful capital Tripoli makes for a great start to explore the country, as it still has its traditional walled medina to explore, as well as the interesting Red Castle Museum, with expositions on all parts of the region's history. Despite the development as a tourist destination, this remains a quintessentially North-African place, with a range of beautiful mosques and impressive fountains and statues to remind of its historic role in the great Ottoman Empire. Some 130 km from the capital is Leptis Magna ('Arabic: لَبْدَة), once a prominent city of the Roman Empire. Its ruins are located in Al Khums, on the coast where the Wadi Lebda meets the sea. The site is one of the most spectacular and unspoiled Roman ruins in the Mediterranean. Another must-see is Cyrene, an ancient colony founded in 630 BC as a settlement of Greeks from the Greek island of Theraand. It was then a Roman city in the time of Sulla (c. 85 BC) and now an archaeological site near the village of present-day Shahhat and Albayda.

The vast Sahara makes for some excellent natural experiences, complete with picture-perfect oases like Ubari. The Unesco listed town of Ghadames was once a Phoenician trade town, and the ruins of its ancient theatre, church and temples are a major attraction today. For stunning landscapes, try the Acacus Mountains, a desert mountain range with sand dunes and impressive ravines. The varied cave paintings of animals and men that were found here have earned the area recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site too.

Do

editBuy

edit| Note: You are not allowed to take Libyan dinars out of Libya. | |

Money

edit|

Exchange rates for Libyan dinar

As of January 2024:

Exchange rates fluctuate. Current rates for these and other currencies are available from XE.com |

The Libyan currency is the Libyan dinar, denoted by the symbol "ل.د" or "LD" (ISO code: LYD). The dinar is subdivided into 1000 dirhams. Banknotes are issued in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 dinars. Coins are issued in denominations of 50, 100 dirhams, ¼, and ½ dinar.

The Libyan dinar is commonly called jni in the (western Libyan Dialect) or jneh in the eastern Libyan dialect. These terms are derived from the "guinea", a former unit of currency in the UK. The word dirham is not used in everyday speech. Garsh is used instead to refer to 10 dirhams.

ATM cards are widely used in Tripoli more other areas and most big name stores and some coffee lounges accept major cards. Check that your card is going to work before leaving major centres as previous networks and ATM facilities may be damaged or missing.

Economy

editThe Libyan economy during the Gaddafi era depended primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which contributed about 95% of export earnings, about one-quarter of GDP, and 60% of public sector wages. Substantial revenues from the energy sector, coupled with a small population, gave Libya one of the highest per capita GDPs in Africa. Libyan Arab Jamahiriya officials made progress on economic reforms in last four years of their administration as part of a broader campaign to reintegrate the country into the international fold. This effort picked up steam after UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003 and as Libya announced that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction in December 2003. Almost all US unilateral sanctions against Libya were lifted in April 2004, helping Libya attract more foreign direct investment, mostly in the energy sector. Libya applied for World Trade Organization membership, reduced some subsidies and announced plans for some privatisation of state-owned companies. The former Libyan government invested heavily in African projects including large scale telecommunications and other major international infrastructure and development programs. Sanctions were re-applied in 2001.

In 2011 actions by domestic insurgents and foreign military forces effectively closed down the normal functions of civil administration during the civil war period.

Eat

edit- See also: North African cuisine

In Tripoli, it is surprisingly hard to find a traditional Libyan restaurant. Most serve western-style cuisine, with a few Moroccan and Lebanese restaurants thrown in. There are also good Turkish restaurants, and some of the best coffee and gelato outside of Italy. There are some wonderful Libyan dishes you should taste in case you are fortunate enough to be invited to a Libyan dinner party or wedding (be prepared to be overfed!)

A favourite café for the local expatriate community is the fish restaurant in the souq. For the equivalent of a few US dollars, you can enjoy a great seafood couscous. A local speciality is the stuffed calamari.

Also recommend Al-Saraya: Food OK, but its attraction is its position, right in Martyr's Square (Gaddafi name: Green Square). Another good seafood restaurant is Al-Morgan, next to the Algiers Mosque, near 1st of September Street.

There are flashy looking big fast-food outlets in Tripoli. These are not quite the multinationals, but a close copy of them. They are springing up in the Gargaresh Road area, a big shopping area in the western suburbs of Tripoli.

Try one of the best local catch fish named "werata" grilled or baked with local herbs and spices.

Drink

editTea is the most common drink in Libya. Green tea and "red" tea are served almost everywhere from small cups, usually sweetened. Mint is sometimes mixed in with the tea, especially after meals.

Coffee is traditionally served Turkish style: strong, from small cups, no cream. Most coffee shops in the larger cities have espresso machines that will make espresso, cappuccino, and such. Quality varies, so ask locals for the best one around.

Alcohol is banned in Libya, though it is readily available through a local black market (anything from whisky to beer to wine). Penalties for unlawful purchase can be quite stiff.

Sleep

edit

Major cities have a range of accommodations available, from shabby hotels to 4-star establishments. Prices vary accordingly.

In Tripoli, there are a couple of international-standard hotels: the Radisson Blu opened in 2009/2010 and offer excellent accommodations and services, while the older Corinthia Hotel, is located adjacent to the old city (The Medina or "Al Souq Al Qadeem"). Other hotels are Bab-Al-Bahr, Al-Kabir, and El-Mahari.

Manara Hotel, a tidy 4-star hotel in Jabal Akhdir, east of Benghazi, is next to the ancient Greek ruins of Appolonia Port.

While it seems to be diminishing with the arrival of more tourists every year, Libyans have a strong tradition of taking travellers into their own homes and lavishing hospitality on them. This is certainly true in smaller towns and villages.

There are several good hotels in Tripoli's Dhahra area, near the church like Marhaba hotel.

Youth Hostels, associated with the IYH Federation (HI), are available. Please contact the Libyan Youth Hostel Association, ☏ +218 21 4445171.

Learn

editWork

edit

Finding a job in Libya is not an easy endeavour, even for Libyan nationals themselves. There are not enough jobs for everyone (Libya's unemployment is between 20-30%) and this forces many Libyans to work abroad in other countries. As is the case in every other country, you must have a work permit if you want to work in the country.

Although the government welcomes investment and help, excessive bureaucracy, high levels of corruption, and political instability mean that many are often reluctant to take up work opportunities in the country. Also, without any knowledge of Arabic, adapting to life in Libya may become a bit challenging. Keep all this in mind if you wish to work in Libya.

Libyan authorities take abuse of Libyan immigration laws very seriously; in 2015, the country outright banned Bangladeshi citizens from entering the country because many Bangladeshi citizens (reportedly) came to the country just to illegally migrate to Europe.

If you have a background in construction, you might be able to find a job in the country's construction sector and be a part of the country's rebuilding efforts. For a country that has been ravaged by open warfare for a decade, much of the country's infrastructure is in desperate need of repair.

Some international organisations, such as the United Nations, are situated in Tripoli. If you have a background in politics or international relations, working in the country won't be such a bad idea. In addition, the country is a great place to further develop your Arabic language skills and make a difference in a country torn apart by years of conflict and instability.

Stay safe

editThe security situation in Libya is fragile and unpredictable. Although some have been brave enough to enter and leave the country without any difficulties, anything can happen in this politically unstable nation.

Crime

edit- See also: Travel in developing countries

Libya has a very high crime rate thanks to years of warfare and instability. Law and order is virtually non-existent in large parts of the country. Foreign visitors are likely to be seen as "easy targets" by Libyan criminals and are likely to be detained for all kinds of reasons.

Don't flash or exhibit objects like cameras, mobile phones, laptops, and so on in public, don't be too trusting of people you don't know, and be aware of your surroundings at all times. In the unlikely event you are robbed, do not fight back, or else you might end up being dragged into a violent fight.

The Libyan justice system is horribly corrupt, fragmented, and inefficient; therefore, if you are the victim of a crime, do not expect the courts to readily prosecute prepetrators and do not expect Libyan law enforcement to take you seriously.

Political unrest

editThe political situation in the country is far from stable.

The first ever presidential election, which has been repeatedly postponed since December 2018, is likely to heighten existing tensions throughout the country. What exactly will happen is open to interpretation.

It is strongly recommended that you regularly monitor local media; you never know what can happen.

Extreme weather

edit- See also: Hot weather

Libya is dominated by the hot, warm, dry Saharan desert; temperatures can rise as high as 50 degrees Celsius. Be sure to hydrate often and wear appropriate clothing to deal with the heat.

Road safety

edit

Driving by most Libyans is wild, and much of the country's road network is poorly developed and maintained. Traffic laws are rarely enforced, and the country has a high road accident rate.

Since much of Libya is covered in vast deserts, wind-blown sand can reduce visibility without warning. In addition, highway signs are usually in Arabic, and roadside assistance is limited. If you don't know Arabic and have no experience with driving in North Africa, it would be better not to drive in Libya.

Terrorism

editAs obvious as it sounds, no part of Libya should be considered entirely safe; the potential for violent incidents, either targeted or random, exists anywhere at any time, and many governments advise that terrorists are likely to conduct attacks in Libya.

Libyan dual nationals

editWomen travellers

editIf you are married to a Libyan, you are subject to Libyan marital laws: your children cannot leave the country unless your (former) husband gives permission. This may make it impossible for you to leave the country with your children if you decide to divorce your Libyan husband.

If you had the misfortune of being married to an abusive spouse and are not prepared to deal with the prospect of never seeing your children again, encourage them to not go in the first place.

LGBT travellers

edit| WARNING: Libya is not a safe destination for gay and lesbian travellers. LGBT activities are seen as severe offences and they are punishable by lengthy prison sentences or death. Militias may choose to execute you without trial instead. | |

As is the case throughout the Arab world and the Middle East, homosexuality is frowned upon by the vast majority of Libyans. Open display of such orientations may result in open contempt and possible violence.

Under current laws, same-sex activity is punishable by up to 5 years in prison. This law, in practice, is rarely enforced because militias may choose to execute LGBT people instead. There are no laws and policies in place that protect the rights of members of the LGBT community.

Photography

editLibya has strict rules about taking pictures. For example, photographing or filming military or law enforcement personnel or installations is a quick way to get into trouble.

Stay healthy

editPrior to the fall of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Libya had an excellent health care system. However, the civil wars that soon followed badly damaged and devastated the once excellent health care system. Many hospitals are in a state of despair and there's a shortage of medical supplies and staff.

Good quality healthcare facilities can be found in major cities such as Tripoli.

Medical care in the most remote parts of Libya is virtually non-existent.

Even if you have travel health insurance it may not be valid in the country. It's advisable to check in advance with your insurer.

Respect

edit|

Ramadan

Ramadan is the 9th and holiest month in the Islamic calendar and lasts 29–30 days. Muslims fast every day for its duration and most restaurants will be closed until the fast breaks at dusk. Nothing (including water and cigarettes) is supposed to pass through the lips from dawn to sunset. Non-Muslims are exempt from this, but should still refrain from eating or drinking in public as this is considered very impolite. Working hours are decreased as well in the corporate world. Exact dates of Ramadan depend on local astronomical observations and may vary somewhat from country to country. Ramadan concludes with the festival of Eid al-Fitr, which may last several days, usually three in most countries.

If you're planning to travel to Libya during Ramadan, consider reading Travelling during Ramadan. |

Much of what is considered good manners in the Arab world is applicable to Libya.

Libyans are indirect communicators. They are tempered by the need to save face and protect their honour and they will avoid saying anything that could be construed as judgemental or negative. One's point is expressed in a roundabout way.

Never beckon a Libyan person directly, even if they've done something wrong in your opinion. Libyans in general are non-confrontational by nature and can be rather sensitive to strong, harsh comments. Under Libyan law, if you are thought to have defamed someone or violated the honour or reputation of someone, you can be taken to court. What exactly counts as "defamation" and "violating someone's honour" is open-ended and subjective, but simply put, refrain from making strong comments about people, even if your perspective happens to be true.

Respect for elders is important in Libya. You are expected to act politely around someone older than you, and it would be seen as rude manners if you attempt to challenge someone older than you. It's commonly expected for the senior-most person to make decisions in the business world. If you come across someone who is older than you, give up your seat on public transportation for them. If you're waiting for a taxi, allow someone older to take your spot. If you're in a business meeting, stand up to greet the senior person. If you've been invited to a Libyan home, greet the elders first.

Libyans take relationships very seriously and they view them as long-term commitments. In the business world, Libyans prefer to do business with those they know and respect and look for long-term relationships.

Always use your right hand when shaking hands, bringing something to someone, and so on. The left hand is considered unclean in Libya. It would be considered impolite to use your left hand to offer something to someone, and it would be seen as awkward to eat with your left hand.

The pace of life in Libya is quite slow. Building relationships and getting things done require you to demonstrate sincere interest as Libyans try to do things in a measured, careful manner. Do not express frustration at this or try to rush things; it can be seen as insulting.

Home etiquette

edit- Libyans are not known for being punctual, which can be very surprising to visitors from countries where punctuality is highly valued. Lateness does not imply rudeness or a lack of interest; people have a casual approach to time.

- If you've been invited to a Libyan home, you will often be showered with tea, coffee, and snacks. Refusing any of these would offend your hosts and it could get them to think that you do not appreciate them or their hospitality.

- You'll often be encouraged by your hosts to take second helpings ad infinitum. If so, take it as a form of respect as it may leave a good impression on your hosts.

- Utensils are not used when eating. People tend to eat with their right hands. As is the case in many Muslim-majority countries, the left hand is considered unclean.

Things to avoid

editPolitics

edit- It is illegal to criticise the country, the state flag, or the state emblem. Doing so is punishable by up to three years of imprisonment. You do not have to praise the country excessively; just be polite. It is also a crime to criticise another country's flag or state emblem on Libyan soil.

- Criticism of the government is unacceptable in any way, shape, or form. Under current Libyan laws, you can be arrested for "insulting" or "disparaging the dignity of" public officials. You never know who you might be talking to. For similar reasons, don't engage in political discussions with people who bring up politics. Again, what exactly constitutes as "insulting" and "disparaging someone's dignity" is open-ended and subjective, but simply put, be careful with divulging your opinions on the country's political situation. Those who have left Libya may be more open to having a political discussion.

- As is the case throughout the Arab world, the Israel-Palestine conflict can be a dicey and highly emotive topic for some people. Unless you have a heart for prolonged discussions, avoid discussions on Israel.

- Avoid having a discussion on Muammar Gaddafi. In some circles, people feel that there was more stability under his rule and may be offended by negative comments about him or his regime. Gaddafi loyalism is still strong in cities like Sirte.

Religion

edit- Islam is the dominant religion in Libya and it plays an important role in the lives of many. During Ramadan, you should refrain from eating, drinking, smoking, and chewing in public.

- It is illegal to criticise or speak badly about Islam. Doing so is punishable by up to two years of imprisonment.

- It is illegal to proselytise any religion other than Islam. This includes possessing religious literature.

Connect

editCope

editConsular services

editDue to various factors − the effects of the civil war, the ongoing humanitarian crisis, the volatile security situation, political instability, and so on − many embassies and consulates offer limited services. Some governments have closed down their diplomatic missions completely.

Most embassies, foreign missions, and provisional offices are situated in Tripoli; some consulates can be found in Benghazi.

If requiring assistance from your nation's consular representatives, it may be possible to seek them out in a country adjoining Libya or from a partnered government if a citizen of an EU state. Australia refers their citizens to the Australian embassy in Rome, while Canada and the United States of America refer their citizens to their embassies in Tunis.

Media

editLibya has numerous newspapers, radio stations, podcasts, and magazines.

News outlets

edit- Libyan News Agency. The state news agency of the Libyan Government. Published in Arabic, English, and French.